One of the most interesting new technologies on the stadium scene is facial authentication, which is basically using a person’s face to verify identity to speed up and increase the safety and performance of game-day transactions, from ticketing to concessions and more.

Though still used by a minority of large public venues, the potential of so-called “biometric” technology has attracted the attention of a majority of venue owners and operators. For those running stadium businesses, biometrics is compelling in part for its ability to speed up transactions and to provide new options for more-secure and more-informative business operations that can be conducted with a smaller number of staff.

According to our most recent Stadium Connectivity Outlook Survey, nearly 47 percent of respondents cited “biometrics” as the fourth-most important initiative for 2025.

Ticketing, concessions and credentialing

So far at stadiums in the U.S., the main use of biometrics — primarily facial authentication — is for verification of ticket purchases. After enrolling in a team or venue program in a process that links a ticketing account to a face (via a selfie upload), customers can enter stadiums by simply looking at a camera, a process that in many cases is much faster than traditional bar-code scanning or “tapping” a device with a stored digital ticket.

A handful of venues are pushing the technology even further, using it to speed up concessions transactions by having fans add a government ID and a payment method to their biometric profile — which allows customers to “buy a beer with their face.”

On the venue operations side, use of biometric technology has also picked up the pace, especially in the areas of credential verification and premium-seating area access. In a move sure to spur follow-on activity, the NFL last year implemented facial authentication software from a company called Wicket to provide fast, secure access to restricted stadium zones like the field, press boxes and staff and team areas. Other venues are quickly adding facial authentication devices to provide more seamless access to suites and premium seating areas, eliminating the need for bothersome wristbands while also reducing the staff needed to “police” premium entry areas.

Top issue: Convincing fans to sign up

While a growing number of fans are showing their approval for the technology by going through the think-ahead process of enrolling in biometric programs, venues deploying the technology say they still see resistance from a majority of attendees, either due to security and data-sharing concerns or simply because fans don’t want to spend the time needed to enroll. So far, venues with aggressive biometric programs said they see greater participation from season-ticket holders and premium customers, who may see more benefits from the process than fans who only come to one or a few events a year.

Venues who are trying to add biometrics to concession operations — which requires a participant to also share a photo of their state ID as well as payment information like a credit card number — are also seeing some resistance for that use, most likely due to the general societal concerns about sharing sensitive personal and financial information.

But fans who aren’t worried are enthusiastic about the services, which can greatly reduce the time spent in entering the venue, and then getting food and beverages during an event. By combining biometrics with other payment-speeding technology like self-checkout terminals or checkout-free stands, venues are able to get concessions into attendees’ hands in a matter of seconds instead of minutes, a process whose speed has been confirmed by Stadium Tech Report in live stadium visits.

Biometrics for security: Another step coming?

At most U.S. venues, biometrics are being used on a very deliberate “opt in” basis for fan-facing systems to encourage attendee participation. Even at the Intuit Dome, where the team and venue prioritize the use of facial authentication for ticketing and concessions, fans can still choose to opt out and use more traditional methods for entering and payment.

But due to security concerns, a more invasive form of biometrics — usually facial recognition systems — may be coming to more venues sooner than later. To explain the difference: In “facial authentication” systems, the setup takes a fan-provided photo and transforms it into a digital token, which is then stored and used for verification, comparing it to a live image of the associated face. Such systems are built to be less personally invasive, since any theft or transfer of the digital tokens will not reveal a person’s face.

Facial recognition systems, however, do take an image of a person’s face and store it, to make comparisons to live images more powerful. Typically, facial recognition systems have been used by law enforcement and other security systems to help identify known bad actors, whose photos may have been taken by public-space cameras whose presence may or may not be revealed.

In some venues in Europe and South America, such systems are already being deployed at large public venues, sometimes under mandate from security or law enforcement bodies. Several U.S. venues have already deployed similar systems, which have been used to identify and exclude persons the venue does not want to let inside, for various reasons. In one U.S. venue a facial recognition system has been integrated with the stadium’s security scanners, to catch known bad actors at a point where they can be most easily apprehended or turned away.

While use of facial recognition technology in general situations like access to transportation systems has sometimes spurred public backlash, venues that decide to deploy such systems may make it a condition of ticket purchase. Events like the mass storming of the gates at the Copa America soccer final last year at Miami’s Hard Rock Stadium — where large numbers of fans without tickets pushed their way past security perimeters, even trying to enter the venue by climbing through the air ducts — may prompt venue owners and operators to look at biometrics as a way to strengthen overall security measures, especially for high-profile events.

In the long term, some proponents of biometrics see the technology as the enabler to a future where all game-day transactions, from ticket purchase to parking to entry to security and on to club access and concessions — are tied to a fan’s identity, all verified by a simple smile. The deeper ties to fans’ detailed demographics and actual in-venue activity is also a huge benefit of biometric systems for teams, who can then use that data to finely tune marketing and ticket-purchase efforts.

Other venue technology professionals simply see biometrics emerging as part of an overall technology stack that can help both attendees and business owners to improve interactions with a shared mix of responsibilities, while recognizing that the systems may not ever appeal to a wide range of fans.

Based on the early success of leading-edge deployments, the guess here is that biometrics will make steady progression in the near term future, especially as form factors and deployment methods become more standardized and more familiar even to casual fans. What follows next are some in-depth descriptions of how each of the systems work, with some real-world examples, as well as short profiles of the leading technology and service providers in the stadium market today.

How it works: Facial authentication for ticketing

In 2021, when Major League Soccer’s Columbus Crew opened its new home, Lower.com Field, it gave fans a unique option: They could tie their Ticketmaster account to a shared selfie of their face, and then be able to use the stadium’s new facial authentication system to enter the venue.

Stadium Tech Report was present for one of the Crew’s early home games that season, and got to witness the system first hand. While overall ticketing technology market-wide has progressed in recent years to speed up stadium ingress [see our previous report on entry technology], it didn’t take too much watching time in Columbus to see how facial authentication systems could support much shorter entry times.

After a sudden thunderstorm kept fans bunched up outside the stadium before game time, big crowds hit the Crew’s entry gates when the all-clear was given. While multiple entry lines and the use of Evolv walk-through security scanners helped move fans into the stadium quickly, the fastest path inside was one of the several lanes using the facial authentication system, using software from a company called Wicket.

At those lines, fans simply strode up to an iPad mounted on a turnstile, and stared at the screen for about a second before it changed to green and welcomed them inside. In that short interaction, Wicket’s software had recognized the face associated with the ticketing account, and verified all the valid tickets in that person’s account. What made the line move even faster was the fact that if one person had multiple valid tickets (for family members or friends), all those tickets were verified by one facial recognition, allowing the friend or family groups to walk quickly in, following the approved ticketholder.

For the fans who used the system, the immediate gratification of faster entry made it well worth the time they had spent beforehand to enroll in the system, a web-based process of uploading a selfie and attaching that image to a Ticketmaster account. Wicket, a Cambridge, Mass.-based startup that had received some early funding from the Haslam Sports Group (a family concern that owns the Crew as well as the NFL’s Cleveland Browns) had developed its system with the teams in order to address one of the biggest Covid-based concerns at the time, that being the long lines that could develop at stadium entry points. The Wicket-based system had been used first by the Browns the year before when there were limited-seating events held at their stadium while the pandemic was ongoing.

“Fans didn’t even have to take their Covid mask off — the iPad would recognize them and they could get into the game safely at a distance without touching phones or anything like that,” said Wicket chief operating officer Jeff Boehm, describing the company’s origins. “So it really was around sort of the the simplicity and public safety of that use case.”

Though most ticket verification technology uses special-built hardware like pedestals, handheld scanners or turnstiles, the software-only developer Wicket found a serendipitous choice in the Apple iPad, which had both the camera and the processing and connectivity power built in to handle the system’s needs. Without having to develop its own hardware platform, Wicket could move more quickly than competing ticketing platforms.

In 2023, Major League Baseball jumped into the biometric ticketing market, with a trial of its “Go-Ahead Entry” technology at the Philadelphia Phillies’ Citizens Bank Park. Since then, the program has expanded to eight MLB stadiums that use the proprietary kiosks that use camera and ID technology from NEC. The program works similar to the Wicket systems, with signup necessary through MLB’s Ballpark app.

Does it deliver as promised?

Fast forward a few years, and what had been a novelty kind of thing is now a very entrenched part of the entry procedure, especially at Huntington Bank Field, home of the Browns. One of the biggest proponents of the technology is Brandon Covert, vice president for information technology at the Cleveland Browns (who also oversees technology at Lower.com Field), who has watched an experiment become a favored process.

“It took us a couple years to go from, ‘this is a cool thing’ to ‘this is really impactful,’ ” Covert said. “But the technology has been proven.”

Indeed, after the 2022 season the Browns released information that noted that the Wicket system had an average entry time of 2 seconds per ticket, an attribute the team said allowed it to clear its entry gates 10 minutes faster on average. From that same press release, the Browns said one Wicket-powered lane could replace four traditional entry lanes, producing a labor and operational savings of $8,000 per Wicket lane deployed.

At the end of the 2023 season, the Browns had 35,000 fans enrolled in their “Express Access” facial-authentication ticketing plan, and Covert said the system regularly supports 15 percent or more of all game-day entries. Wicket deployments soon started showing up at other large professional venues, including Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, and Citi Field in New York, home of the Mets.

A partnership with Verizon helped fuel even more Wicket deployments, including at Nissan Stadium in Nashville. In addition to speeding up lines, facial authentication systems can also provide space for sponsor activations, with Verizon’s name attached to the entry spots in Cleveland and Nashville. At Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the Wicket lanes are labeled as “Delta Fly-Through Lanes,” sponsored by the hometown airline.

As more stadiums start to embrace the Wicket solution, competitors are racing to catch up. While none have yet secured a public deal with a U.S. professional venue, a few international firms have publicly declared their intentions to offer facial authentication ticketing sytems (see profiles below), with several live deployments at stadiums in Europe and South America. And last year Clear, the company known for its airline identity-verification operations, was revealed to be the technology provider behind the age-verification process for Intuit Dome’s facial authentication systems for ticketing and concessions.

For now, Wicket leads the race for facial authentication ticketing, a fact underlined by the news (reported first in our entry technology feature) that almost all of the traditional ticketing hardware providers are either developing or have developed support for Wicket’s facial authentication in their systems, by adding a camera or enabling camera devices already in place.

Whether the future sees teams and venues trying to turn completely to facial authentication, like Intuit Dome, or for partial use, like Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the bet is that the technology’s attributes for both fans and venue owners and operators will win more converts over time.

“We tried to do a great job holistically around the building and making sure that however you enter, we get you in fast,” said Karl Pierburg, senior vice president and chief technology officer for the Atlanta Falcons, who currently see about 8 percent of Falcons fans using the biometric systems per game. “And this is just one of those means.”

Biometric payment systems crank up the concessions speed

Getting inside a stadium quickly using biometrics may be a welcoming benefit. But getting concessions in seconds instead of minutes may be the biometric gift that keeps on giving — for both fans and venues.

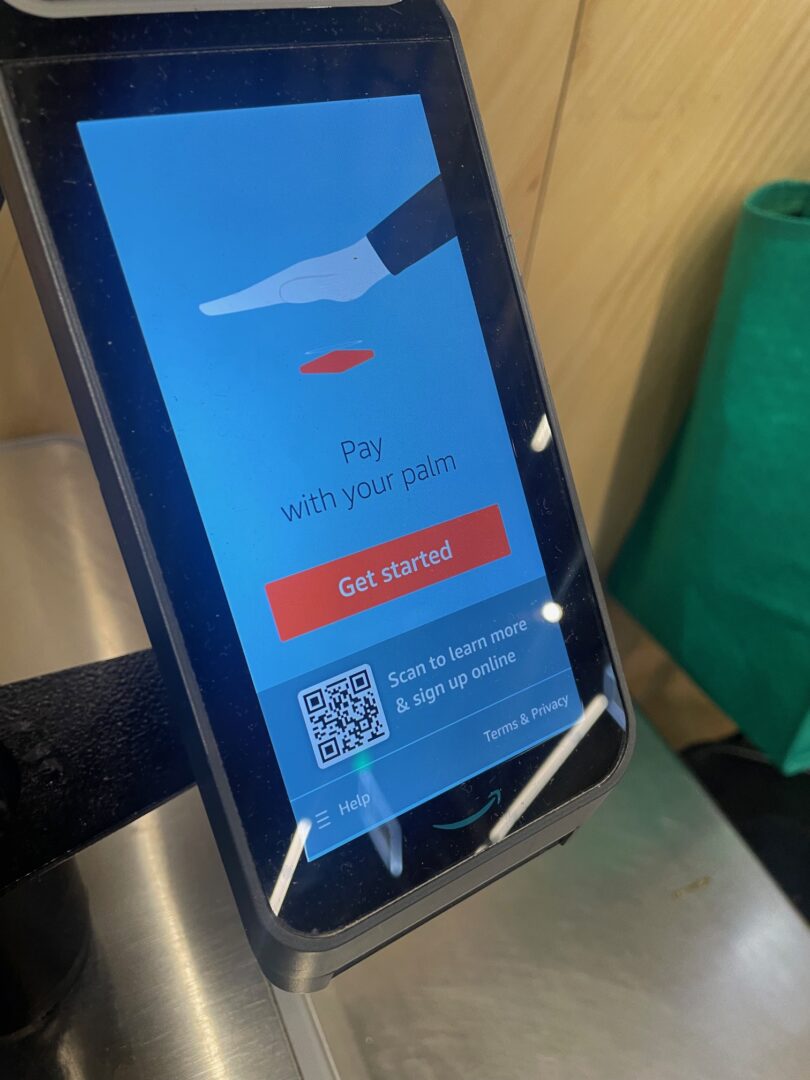

As venues turned to technology to improve concessions operations in the wake of the Covid pandemic, it was inevitable that biometrics would be given a try. One of the earliest active proponents was Amazon, which installed its Amazon One palm-based biometric systems at some of its “Just Walk Out” checkout-free stadium concession stands. People who enroll in the Amazon One program use their palm for identity and payment verification, hovering it above a special-purpose device.

What seems to be gaining more favor in the past couple years are facial authentication-based concession payment systems, now in use in a growing number of stadiums including those in Cleveland, Atlanta, Denver, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Miami. While Wicket is in the lead in such deployments, the space is already attracting competition from Clear as well as from an arm of banking giant JPMorganChase, which has deployments in two venues.

With all the new time-saving technologies arriving at stadium concession stands, why would biometrics be necessary? Stadium Tech Report, in live reporting at several venues, found that while checkout-free and self-scan technology could offer substantial transaction-time improvement over old belly-up lines, all the technologies still required customers to negotiate payment and ID verification, the latter usually with a live staff member.

The combination of payment processes, either by card swipe or tap, and ID verification, we found, could sometimes take up to a minute or more, especially for first-time customers unfamiliar with the devices and the individual store setups. So while the new-technology stores were likely still faster than a belly-up stand, when other things are fast, you tend to really notice the parts that slow you down.

“The ID check was really bottlenecking the fast experience,” said Alicia Woznicki, vice president of design and development at Aramark Sports + Entertainment. “We wanted to see how fast we could make it.”

How it works: Buying a beer with your face in Cleveland

To that end, Aramark was behind two of the leading trials of facial authentication technology for concession payments, first with the Cleveland Browns and then with the Denver Broncos. In Cleveland, Aramark and the Browns debuted a system in 2022 called “Cleveland Cold Ones” where fans could use a mobile app to order a beer, and then go “pay” for it by staring into a Wicket-powered tablet at the stand where they had placed their order. To participate, fans had to enroll in a program like the team’s ticketing system, with the additional asks of a photo of a government ID and payment information (usually a credit card number), so the system could verify payment and age.

For the 2023 season, the Browns, Aramark and their partners expanded the program and made it a walk-up service instead of a mobile app. In addition to the Wicket software, the components for the “Express Beer” stands used during the included age and ID verification services from a Boulder, Colo.-based company, IDmission; point-of-sale and menu software from a Pasadena, Calif.-based company, TapIn2; and credit card verification and fan loyalty information systems from Lava.ai, a San Francisco-based startup. According to Aramark, it blended the components using existing integration APIs from all the providers.

Reaching a total of approximately 5,000 transactions for the entire 2023 season, the Express Beer program more than doubled internal expectations. In 2024 the new program expanded to include not just beer but full menus from 12 different locations throughout Huntington Bank Field.

Ten of these stands are permanent structures in concourse locations, with express lanes for facial authentication customers and regular lanes for other customers. The joint access for Express and non-Express customers allows any fan to use the stands for purchases while preserving the “express” amenity of the facial-authentication program.

The Express Lanes have a branded walk-through gateway with an iPad at the front, where customers can verify that they are indeed enrolled in the system. In the first couple years, Aramark and the Browns encountered more than a few customers who tried to use the “Express” systems even though they hadn’t signed up. With a large QR code on the side of the gateways, the system provides fans with information on how to sign up on the spot.

Once inside, customers select their items from a grab-and-go layout and proceed to the payment and checkout systems, which are all equipped with cameras for facial authentication. During the 2024 season Aramark and the Browns used a mix of optical-recognition checkout terminals from Mashgin (which scan selected products with a camera) and self-scan kiosks powered by TapIn2. With payment and age verification performed through the system, the only human contact needed is to make sure cans and bottles are opened before customers leave the stand.

How it works: Making checkout-free even faster

At Denver’s Empower Field at Mile High, Aramark had bet big on checkout-free concession stands, eventually deploying nine stores with technology provider Zippin. Then in 2023, Aramark, Zippin and the Broncos teamed up to make the fast-transaction stands even faster by adding the ability to use facial authentication to gain entry.

If you’re not familiar with checkout-free stores, here’s a quick primer. Customers are allowed to enter gated stores by scanning a credit card or some other pre-authorized payment method, and by showing an ID for alcohol purchases. After entering they simply take the items they want and then exit. Payment takes place online after they leave the store.

Again, even though checkout-free stores are among the fastest ways to get concessions, first-hand observation by Stadium Tech Report saw many times where customers could spend up to a minute or more at the entry gates, figuring out the payment process and showing an ID to a live person. In fact, many times the payment/ID process took longer than the actual shopping.

On paper it might not sound like a big leap, but from what we observed at a 2023 Broncos game, being able to skip the number of variables that might pop up from ID checks and payment verifications can provide a huge improvement in overall transaction speed of getting into the stores, from half a minute or so to just a few seconds. The Denver “Digital ID” operation uses only software from IDmission.

Another venue using Wicket for concessions operations is Mercedes-Benz Stadium. There, a provider named Spirited combines the Wicket authentication system with a dispenser to let you select your favorite drink, which is then poured automatically. Wicket is also being used for facial authentication concessions operations at BMO Stadium in Los Angeles.

At Intuit Dome in Inglewood, Calif., a similar facial authentication setup is used to gain entry to the checkout-free concession stands, for the fans who have enrolled in the facial authentication system. Clear provides the technology for the age verification part of the system, while AiFi is the provider for the checkout-free stands at the stadium.

Another entrant to the stadium facial authentication concession market is J.P. Morgan Payments, which is an arm of JPMorganChase, the largest bank in the world. J.P. Morgan Payments has had two stadium store deployments, one a recurring merchandise operation at the Miami F1 race and the other at a barbecue restaurant stand at Chase Center in San Francisco. Both deployments use ID verification technology from a company called PopID.

Do the systems deliver, and are fans using them?

In Cleveland, after the first two games of the 2024 NFL season facial authentication purchases accounted for an average of 11 percent of all transactions at the new stands, with two stands showing 24 percent of facial-authentication transactions recorded in the crush time before kickoff, according to the team and Aramark. A full 30 percent of facial authentication transactions during those games were from repeat-customer transactions.

According to the Browns, after those first two 2024 home games there were 6,476 fans enrolled in the concessions Express Access program, with 2,604 of those signups taking place since the start of the season.

By October of the 2023 NFL season, there had been almost 10,000 customers who have signed up for the Digital ID program in Denver, according to IDmission. Aramark added that 35.8 percent of customers who signed up had used the facial authentication system at least two times during that time period.

Amazon, Intuit Dome, Clear and J.P. Morgan Payments have not provided any statistics for the stadium use of their biometric offerings.

Proof positive: Facial authentication for credentialing

Besides ticketing and concessions, another area of activity in stadiums that lends itself well to facial authentication is credentials verification. For staff, media and team member access, venues have long relied on a system of physical credentials, either magnetic cards or plastic cards on neck lanyards, to allow verified participants into sensitive stadium areas like the playing field or court, locker, interview and media rooms, and secure operational areas.

Manual checking of credential type and the need to sometimes match a face to a static photo is part of the longtime staffing activity needed to support such security operations. Similarly, physical credentials have also been a traditional method to verify add-on access permissions, like paper wristbands for premium seating and club areas or hospitality tents.

Facial authentication technology, as it turns out, is a well-received replacement for many of the previous credentialing systems, for multiple reasons on both the user and administrative ends. For teams and venues, the ability to more accurately match a live face to a stored identity provides a higher level of access confidence, and completely eliminates the problem of physical credentials being lent (or stolen) to a different person than they were issued to. For participants, being able to quickly gain access to secure areas without having to deal with lanyards or wristbands is likely to gain more favor as more such systems are deployed.

The flexibility of a digital-based system also allows for timed access periods, like allowing media on playing fields before and after games but not during the actual event. This past football season, the NFL deployed a Wicket-based facial authentication system at all 30 league stadiums for media and staff access. The league has also used a different facial authentication system for media and staff at the past several Super Bowls, using entry technology from Fortress.

Though we have yet to report on any actual deployments of facial authentication systems being used for club or suite spaces, ticketing technology firms are actively developing more digital methods for access to such environments, including devices that can lock and unlock doors, a feature that will help cut down on staffing needs. Wicket has had its technology used by the PGA at some recent golf tournaments, for faster access to premium hospitality areas.

Facial recognition: For higher levels of security

If there is one area where U.S.-based venues trail other parts of the world, it is in the use of facial recognition technology. Unlike the “facial authentication” systems used by most ticketing and concession deployments, true facial recognition systems take and store actual photos of peoples’ faces, often without their knowledge.

Such security systems have been in use for many years in social settings, especially at places like airports, transportation hubs and city centers. While their use in such areas has been challenged at times by social- and civil-rights proponents, the growing use of such technologies in venues seems to have a higher level of approval, since most event attendees are in favor of more-secure situations.

In both European and South American soccer venues, facial recognition technology is used to track bad actors and to deny those people access to events. In one notable event last year, facial recognition systems at a Brazilian stadium identified a crime boss wanted by police in the stands at a game, with police arresting him at the contest. Mostly, the systems are in place to spot fans who have committed previous stadium crimes or unwanted acts, to ban them from entering another event.

While U.S. venues historically have not had to deal with the kinds of fan disturbances that are more common internationally, more venues will likely be looking to deploy such technology in the near future, especially as the U.S. hosts more international events. Some stadiums are already moving in that direction. At BMO Stadium in Los Angeles, a facial recognition system tied to the venue’s new security scanners recently spotted a person who was previously banned from the stadium, and denied that person entry.

While use of facial recognition technology in general situations like access to transportation systems has sometimes spurred public backlash, venues who decide to deploy such systems may make it a condition of ticket purchase. Internationally, some leagues and countries are already making the technology a necessity for venues of a certain size. It is a good bet that more security systems using facial recognition will soon be added to the most visible U.S. venues, especially those that are set to host matches for the 2026 men’s World Cup and the 2028 Olympics.

Conclusion: Biometrics is here to stay, and will likely expand as products and services get better and more well-known

Biometric technology in stadium situations is likely to gain more acceptance as more systems are deployed and they become more secure and dependable. Like the Covid-induced move to all-digital ticketing, some future deployments of biometrics may be required by venues, a change from the opt-in format of most current U.S. stadium deployments.

While some event attendees may still try to avoid biometric solutions, the majority of fans probably will accept that the technology enables faster, safer transactions and hopefully a more secure, safer venue that is harder for bad actors to access. While this change is not going to happen overnight, there will likely be a steady progression to more tasks where biometrics can make game day life easier and a better business for all involved.

Who are the players

Wicket

In the span of just a few years, a Cambridge, Mass.-based startup named Wicket has turned many heads in the stadium entry technology business with its facial-authentication identity verification software. The Cleveland Browns, the Atlanta Falcons and the New York Mets were early customers, and have been followed by several more NFL teams and the league itself, which in 2024 selected Wicket as the technology base for the back-of-house credentialing system installed at all 30 NFL stadiums to better secure access to on-field, press box and other sensitive areas.

Wicket technology is also being used to allow facial authentication for concession purchases, including the ability to verify age and payment processing through partner programs.

Amazon

Amazon has introduced its Amazon One palm-based biometric technology in a number of stadium concession stands and bars. The system uses a flat screen that customers hover their palms over for identification verification. While it is mainly deployed for concession-stand purchases, Amazon One has also been used in some trials for ticket verification. The Amazon One technology is also offered as a payment system at many of the company’s Whole Foods grocery stores.

IDmission

The Boulder, Colo.-based IDmission has a long history of providing online biometric verification software and systems, developed primarily to help financial institutions onboard customers and confirm transactions. Two of the first uses of facial-authentication systems for concessions in stadium situations have turned to IDmission to power their device-driven age and payment verifications, allowing for a much faster customer transaction than face to face interactions.

PopID

The Pasadena, Calif.-based PopID is a startup that develops face- and palm-based biometric technologies for identity and payment verification purposes. In the stadium world, its technology is used by J.P. Morgan Payments for facial-authentication stores at Chase Center in San Francisco, and at the F1 races at Miami’s Hard Rock Stadium.

Clear

Clear, a company known for its identity verification platforms at airports, provides the age-verification technology for the Los Angeles Clippers’ alcohol purchases at Intuit Dome. The technology works inside the Clippers’ “Game Face ID” app, which supports facial authentication verification for ticketing and concessions purchases.

Major League Baseball

One of the more curious entrants in the biometric technology marketplace is not a vendor company but Major League Baseball, a U.S. professional sports league. After some tests with the Philadelphia Phillies in 2023, last season MLB rolled out its “Go-Ahead Entry” facial authentication ticketing systems at six MLB stadiums, as well as in another test deployment at the All-Star Game in Arlington, Texas. Two more teams started using the systems at the beginning of the 2025 season.

The large, purpose-built pedestals (called “monoliths” in MLB descriptions) contain a much bigger camera than other facial authentication systems, designed to be able to capture fans’ faces from a farther distance and without forcing them to stop. MLB has not yet announced any plans to make the systems available outside of MLB stadiums.

J.P. Morgan Payments

J.P. Morgan Payments, which is an arm of JPMorganChase, the largest bank in the world, has two facial-authentication trial deployments at stadiums, one at Chase Center in San Francisco and the other at the yearly F1 races at Miami’s Hard Rock Stadium. The company uses PopID for its biometric technology, and is developing a line of purpose-built biometric-enabled payment platforms for retail outlets.

Veridas

The Navarra, Spain-based Veridas is a provider of a wide range of biometric identification systems, including voice, facial and scanning systems. In the stadium world, Veridas has developed a facial-recognition verification system for multiple stadium applications, including ticketing, security and concessions. Veridas has stadium customers in Spain, Argentina and Chile.

Imply

The Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil-based Imply offers a wide range of technology for public buildings, including LED displays, self-service ATMs and also facial recognition technology for ticketing and concessions operations. This year, the the José Pinheiro Borda Stadium in Porto Alegre, Brazil, also known as Beira-Rio, deployed Imply-powered facial recognition technology at all of its entry gates.