As it turns out, the lopsided score on the football field at Super Bowl 59 on Feb. 9 wasn’t the only blowout that took place in Caesars Superdome that night.

In the wireless community, the competition at the NFL’s championship game was between the fan-facing cellular and Wi-Fi networks. In surprising fashion it wasn’t even close. The combined AT&T and Verizon cellular traffic numbers of 67.1 terabytes eclipsed the night’s Wi-Fi data usage total, 17.2 TB.

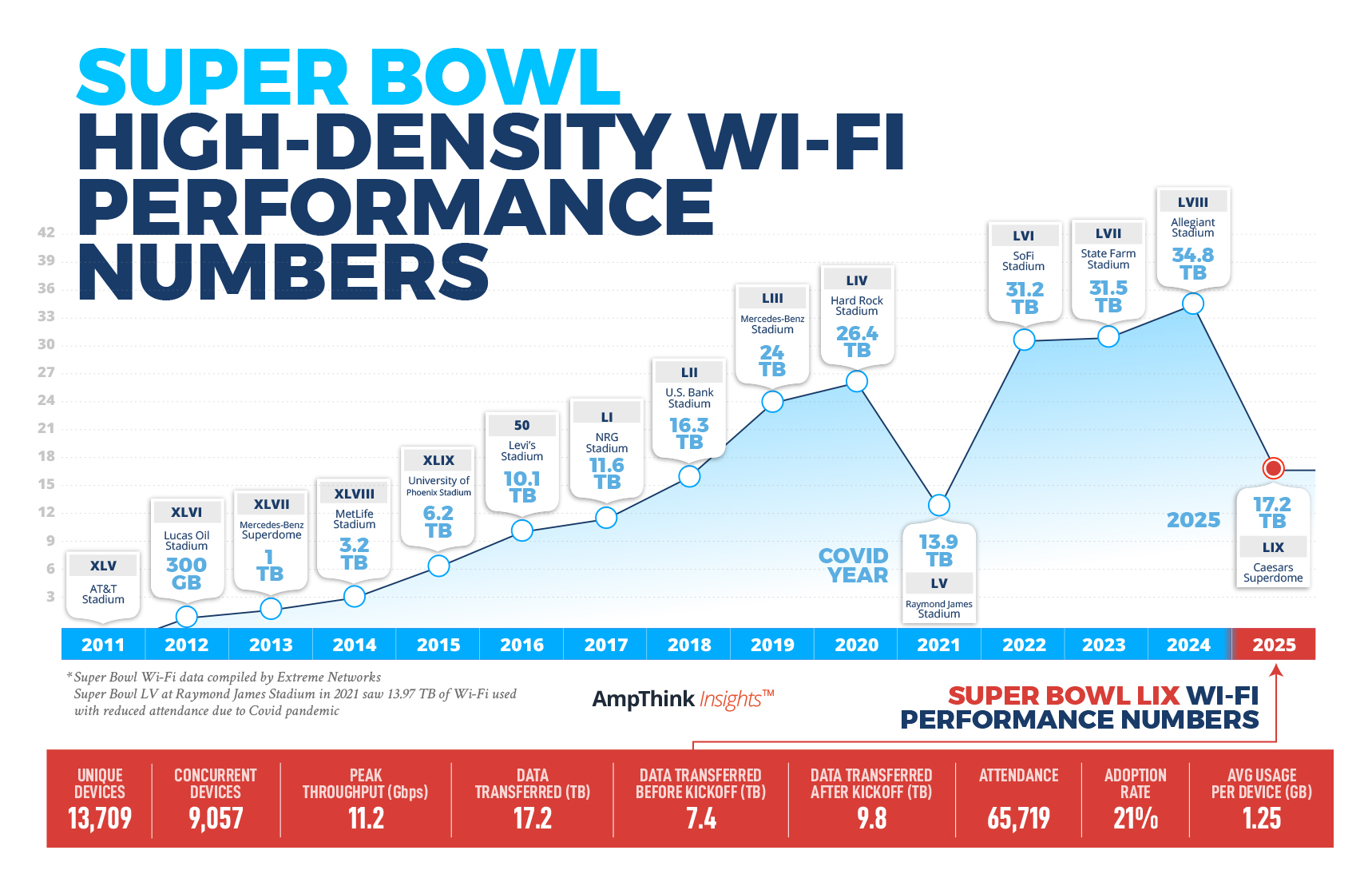

Historically, stadium Wi-Fi totals for Super Bowls have grown steadily, increasing year over year since high density Wi-Fi networks were introduced at Super Bowl XLVI in 2012. The only dip occurred in 2021 at the reduced-attendance Super Bowl LV held during the Covid pandemic. In prior years cellular carriers elected not to provide in-venue Super Bowl stats because they were far lower than the Wi-Fi totals.

Super Bowl 59: Less than half the Wi-Fi total of Super Bowl 58

Super Bowl 59’s Wi-Fi total was less than half the amount seen at prior event at Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas which set the record for most Wi-Fi seen at a Super Bowl. This year, Verizon did provide somewhat in-building specific cellular user numbers, claiming approximately 34,381 fans were on their network, consuming 38.1 TB of data. By comparison, the Wi-Fi network at Caesars Superdome only attracted 13,709 clients of an announced attendance of 65,719. AT&T, the DAS operator, said it saw 29 TB of usage on its networks that night.

While cellular and 5G proponents were quick to seize upon the “victory” on social media, proclaiming it the end of stadium Wi-Fi, the details from behind the scene paint a more complex reality — perhaps a one-time anomaly, specific to New Orleans and the Superdome.

Initial results prove that a robust cellular deployment can handle the traffic demands of a Super Bowl-type event. But noting the disparity between the cost of DAS and Wi-Fi systems in general, is the question going forward “DAS or Wi-Fi” or how to best combine the available options? Shouldn’t venues be asking which technology provides most cost effective solution for the best fan experience?

Poorly configured Wi-Fi, not old equipment, was the issue

What really happened with the Wi-Fi at Super Bowl 59? Our sources report that the excuse provided by Extreme Networks alongside its release Monday of the official Super Bowl Wi-Fi data was incomplete. In an email announcing the results Extreme stated, “Our belief is that the combination of the older network components in the stadium, combined with a hefty investment in a 5G deployment by Verizon, created an unusual and atypical usage pattern of 5G versus Wi-Fi.”

We previously reported on investments in the DAS at Caesars Superdome. Carrier investments may have diverted traffic from the Wi-Fi network. But putting a big part of the blame on the older Wi-Fi gear for the poor Wi-Fi numbers isn’t correct. As we learned, any older gear in the network, mostly Cisco equipment from a previous deployment, was only deployed outside of the venue. Inside the dome, a new deployment of HPE/Aruba Wi-Fi 6E gear using approximately 2,500 APs was installed ahead of the game, mostly under seats.

Sources who desired to remain anonymous told STR that issues with the Wi-Fi deployment also contributed to the poor performance. The sources said that the problem was identified during an independent Wi-Fi audit conducted several months before the event. The issues were believed to be unresolved at game time.

Making the story more interesting is a rumor that Verizon was initially awarded the Wi-Fi deployment contract ahead of the Super Bowl, but declined when the proposed contract stipulated they use a local contractor. After Verizon’s withdrawl, the the Wi-Fi upgrade was awarded to the same local contractor, a firm with no previous Super Bowl experience.

Another factor contributing to low stadium Wi-Fi use was the absence of Verizon’s offload SSID, a big traffic driver of Wi-Fi attachment at prior Super Bowls. Neither Verizon, the stadium operator, ASM Global, the local contractor nor the NFL responded to requests for more information about the Wi-Fi network deployment.

Verizon’s pack-the-house response and a possible issue with Wi-Fi 6E

What gives the Verizon withdrawl from the Wi-Fi upgrade contract rumor some legs is Verizon’s response to the situation, which was to “pack the house” with more wireless gear than deployed at prior events. In addition to the complete rip and replace of the existing stadium DAS by AT&T — which Verizon shared use of — Verizon put in an extra 511 ultra-wideband 5G antennas and 155 C-band specific antennas, according to the company.

Industry sources estimated that the cost of the combined Verizon and AT&T cellular upgrades to the Superdome networks could have been more than $50 million. Verizon execs told Stadium Tech Report that they have been adding more resources to Super Bowls ever since the stadium Wi-Fi at Super Bowl 57 suffered from an outage. But the massive install of additional equipment at Caesars Superdome this summer, in advance of the event, suggests that Verizon knew ahead of time that the stadium Wi-Fi was not going to be reliable.

Another issue contributing to poor Wi-Fi usage may have been issues with the adoption of the relatively new Wi-Fi 6E — a work in progress. Wi-Fi 6E uses a 6 GHz spectrum swath that is almost 3 times larger than what is available in 5 GHz and discovering these services can be a challenge. Discovering 6 GHz service generally begins with attachment to the 5 GHz spectrum. Any disruption within 5 GHz services could inhibit transitioning to 6 GHz services.

Another possible issue with devices utilizing Wi-Fi 6E 6 GHz services are reports of “sticky” associations. Sticky clients discover a sub-optimal connection and then don’t move to a better connection when their location changes. With only a handful of stadium-sized Wi-Fi 6E networks running anywhere, the ongoing list of potential configuration issues is far from being resolved.

Looking beyond the reduction in total Wi-Fi volume, the event did see a new record set for per-device bandwidth usage. With fewer users on the network, those who did connect were able to use an average of 1.25 gigabytes of data per device, besting last year’s 788 Mbytes average per user at Allegiant Stadium. On Verizon’s network at Super Bowl 59, the average per-device usage was 1.06 GB per device.

How did Stadium Tech Report score the wireless war at Super Bowl 59?

Winners

- Verizon, for seeing what was happening with the Wi-Fi and doing what was necessary to ensure its customers had a good experience

- AT&T, for stepping up to direct a full DAS rip and replace

- MatSing, for having boatloads of its lens antenna gear purchased by both Verizon and AT&T

- Verizon and AT&T customers, beneficiaries of their providers’ investment

Losers

- The Wi-Fi community, since each failed deployment is an indictment of Wi-Fi’s suitability for supporting large scale events

- ASM Global and its local partner, for delivering an underperforming Wi-Fi experience

The reality of cellular stadium over-investing — it isn’t for every venue

At Stadium Tech Report we like to say that when it comes to Super Bowls, for cellular carriers there is no such thing as a “budget.” Given the high promotional value of the NFL’s biggest game, it’s perhaps understandable that the leading U.S. carriers would always spend what is necessary to ensure that their top customers will never get the dreaded no-signal available message while attending the event. So if your venue is hosting the Super Bowl, relax, because your DAS will always be taken care of.

But to those who would say cellular-only is the preferred stadium wireless configuration of the future, we simply would ask how readily would Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile invest in 5G for venues not hosting a Super Bowl or a World Series or some other “jewel event?”

While NFL-size venues might always have some kind of DAS deployment, smaller Major League Baseball parks, NBA/NHL arenas and MLS stadiums might encounter some difficulty in getting carriers to buy in. In fact for some of the new soccer stadiums we’ve seen built in the U.S. the past few years, opening day arrives with an active stadium Wi-Fi network but no carriers on the DAS as those negotiations stretch on.

Tired of having been “overcharged” for DAS contracts over the years, the carriers have been very public the last year or so about saying they simply won’t participate if a DAS deal asks too much for rent. And while the stadium wireless industry also has its Wi-Fi-only proponents, the truth is (and has always been) that a hybrid solution of both cellular and Wi-Fi has proven to typically be the configuration that provides both the best fan and business connectivity experience, while also being more economical for all parties involved.

New conversations: Seeking the best experiences, not the highest numbers

If you are looking for guilty parties who have publicized specific wireless traffic numbers in big headlines in the past, we here at Stadium Tech Report will be the first to raise our hands. Early in the game of stadium wireless, reporting “big” Wi-Fi days at venues was a way we saw to prove the potential of stadium Wi-Fi in a simple statistic that everyone could understand.

But if you’ve paid attention you might have noticed that our “Top 10 Wi-Fi Events” lists are a thing of the past. We still do like to keep our chart of Super Bowl Wi-Fi data totals going, if only because of the historical perspective it offers. When Levi’s Stadium hosted Super Bowl 50 back in 2016, the total of 10.1 TB of traffic recorded was a stadium Wi-Fi watershed moment, certifying the effectiveness of under-seat antenna deployments by almost doubling the Wi-Fi total from the year before.

Next year, we fully expect Levi’s Stadium to post a mark that continues the steady upward path of Super Bowl Wi-Fi growth, but if we learned anything this year it’s that we should also allow for the possibility of cellular networks taking over more of the total share of traffic. As much as we’d like to have that conversation, to get there we will need some kind of Geneva convention on statistic reporting before then, because historically the carriers have not been as forthcoming or exact on the statistics they provide as the stadiums and Wi-Fi.

But with better and more uniform ways to measure wireless networks in general, we might also be better able to agree on what combination of technologies, providers and venues can produce a better wireless experience, both from a user perspective as well as from the view of those who spend the money to make the networks available. In our conversations with Verizon this year the carrier execs told us of how network use at Taylor Swift concerts at the Superdome this fall saw more upload than download traffic, a switch they said would inform the way they configure stadium networks going forward.

Maybe a different conversation that happens with combined services in mind is if the general network provider should pay for users who want to do bandwidth-extraordinary things like continuous live streaming. Could some combination of Wi-Fi, 5G and diverse offload choices between the two make it easier to provide premium bandwidth connections where those who want more could pay more for the privilege? What happens when more Passpoint deployments arrive, where carriers may no longer be the entity that decides which network a client might use?

With smarter and more equitable insights into stadium network traffic, all the parties involved in the delivery and use of venue wireless deployments might be able to better reach a place where the best overall network experience is the goal that is celebrated, and not the temporary and asterisk-ridden “victory” of a high bandwidth number.